Upper Gardner Street

Lead Researcher - Ian Walden

1. Introduction

For six days each week Upper Gardner Street gives every impression of being a quiet, slightly neglected backwater within the North Laine. Linking North Road in the south to Gloucester Road in the north, Upper Gardner Street itself contains no particularly distinctive or fine buildings and many of the original houses have been demolished and replaced in the recent past.

However, arrive during the weekly street market on a Saturday morning and one finds a hub of lively commercial activity, a reminder that, throughout its history, this little street has provided a practical and down-to-earth focus for the community’s social and trading life, which is the subject of this exploration.

Readers interested specifically in the street market should refer to section 6 below, 'Residents' (under Harry Cowley), and section 8, 'Trade'.

2. Development

The 1792 land survey of Brighton, known as the ‘terrier,’ showed five tenantry ‘laines’ or large open-plan fields. Named West Laine, Little Laine, East Laine, Hilly Laine and North Laine, they surrounded the town of Brighthelmstone, the old name for Brighton. The North Laine was divided into furlongs, each of which was sub-divided into narrow strips called ‘paul-pieces’ running north to south. The modern-day street pattern in the North Laine area is based on the boundaries of this open-field system.

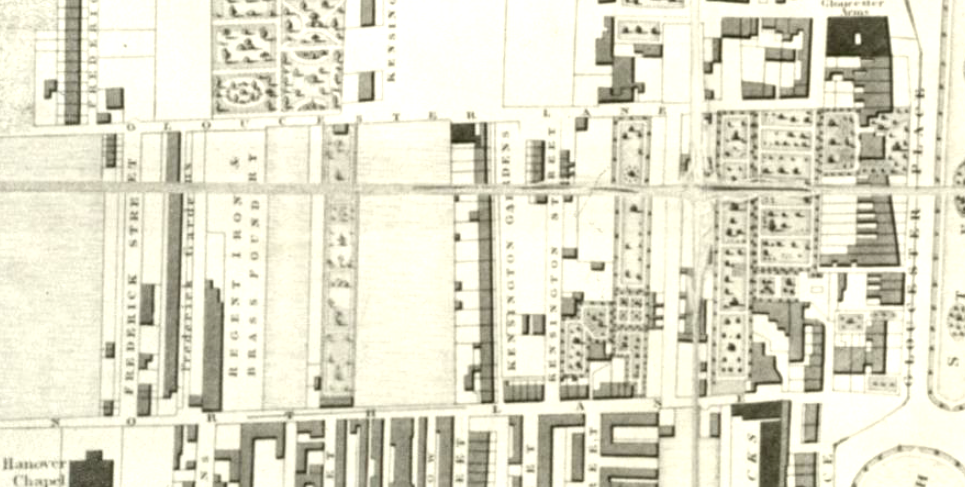

The J Pigot Smith map of 1826 shows development of the North Laine well underway, including the old Second Furlong, in which Upper Gardner Street was built. Full streets of houses were already built in nearby Kensington Gardens and Frederick Gardens, and the Regent Iron & Brass Foundry dominated the area, but Upper Gardner Street was then still an open field. Development would not take long; laid out under the ownership of Thomas Read Kemp (of Kemp Town fame), and sold or leased in small parcels to developers, the street was developed in the following decades and by the 1841 census the street was home to 174 inhabitants.

Pigot-Smith map of Brighton, 1826.

Kensington Gardens is in the centre of the map; Upper Gardner Street would

later be built on the open ground immediately to the East.

Image courtesy of Brighton History Centre

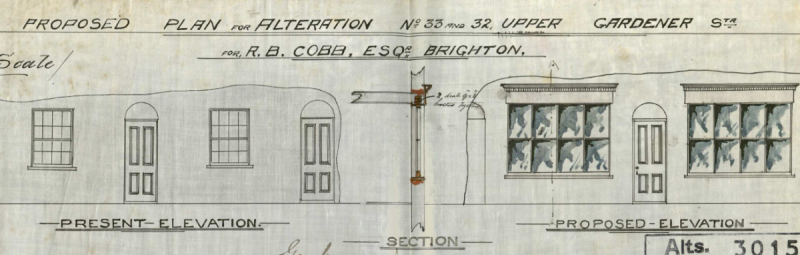

The first detailed picture of the street’s buildings appears in the 1876 Ordnance Survey maps and shows a layout familiar even today. Our earliest records of building extensions and improvements are from the following decade, with plans dated June 1881 for a new top storey (the second floor) on nos. 25 & 26 Upper Gardner Street, 31 Gloucester Road1 and a first-floor extension at the rear of number 22.2 Those buildings were purely residential, but by 1890 Mr R B Cobb had enlarged the windows of his properties at nos. 32-34 (previously small eight-over-eight sashes like those still seen at no. 35), all of which housed shops or stores on the ground floor, presumably to showcase the goods for sale within.3

Plans for alteration, nos. 32 & 33 Upper Gardner Street

The 1935 Brighton Rate Book demonstrates that the highest-value properties in the interwar years, unsurprisingly, were those owned by Messrs. Durtnalls Ltd; the “office, workshop, and stores” at nos. 1-2, the “van shed and workshop” at nos. 3-4, and the “warehouse, stores, and stabling” at no. 39. Numbers 40-41, to the left of the School, were then a “garage and stores” run by Grace Roberts Ltd. No less than eight premises are described as “house and shop” (nos. 7, 11, 20, 27, 28, 32, 33, and 34). This number includes neither of the street’s 2 sometime pubs, the Heart and Hand on the corner with North Road, and the Forester’s Arms at no. 21 (closed c.1906).4

By mid-century much of the street’s housing had fallen into disrepair and was increasingly undesirable. The scale of the problem can be gleaned from a memo in the Borough Corporation’s files relating to their purchase of no. 19 in 1957. Written by the Medical Officer of Health and dated 18th July 1957, it states that “originally the whole of the east side [of UGS] was scheduled as unfit [for human habitation], but some properties have been improved and the present position is as follows:-

Nos 5, 6, and 7 – unfit

Nos 8-14 – unfit; already in a confirmed Compulsory Purchase Order and awaiting demolition

Nos 15-18 – unfit, but No. 15 is “borderline” and No. 18 is undergoing repair at the moment and may be made fit

No 19 – fit

No. 20 – unfit

Nos 21, 22, 23 – fit, but 23 is “badly arranged”, and may be included in a clearance area for that reason

No. 24 – unfit

… Whether any house is to be included in a clearance area will, of course, depend on its condition at the time of representation.”5

Built to the standards of a century earlier and rarely owner-occupied, few properties had indoor toilets or bathroom facilities outside the kitchen and many were afflicted with damp, sagging walls, dry rot or woodworm. All these problems were present at nos. 32-33, which underwent extensive renovation in 1967, including rebuilding and re-rendering a bulging front wall, removing two chimneys, damp-proofing and re-plastering all internal walls, replacing a staircase, major repairs to roof timbers and slates, building a kitchen and bathroom extension to the rear, adding a new door, gutters, drains, and all new windows.6

In the case of no. 19, the Corporation completed their purchase of the property in June 1958, intending it as an addition to their council housing stock. However, extensive repairs would be required before this could be achieved and whether these were attempted or not, this property was added to the ‘unfit’ list in 1963, boarded up, and deemed useful only for storage. Even in 1966, the next-door neighbour, a Mr Luckman of no. 18, was still having to complain about the dangerous state of no. 19’s wall, the noise and smell of pigeons entering through unglazed or broken windows, and the property remained in dilapidated state at the file’s conclusion in February 1970!7

Meanwhile, by January 1962, the Corporation owned all of 8-14 Upper Gardner Street, and all were vacant apart from no. 13, rented by Mr E H Cowley (who would be given no. 27 in lieu when no. 13 was boarded up; see ‘Ownership Patterns’ below). These properties’ slates and cement had been falling onto the industrial premises (formally Tucknott’s Printing works) at nos. 7-8 Kensington Gardens, then owned by John Blundell Ltd., who were repeatedly having to call their manager out because of damage caused.8

Eloquent testimony to the effects of neglected buildings and the imminent threat of demolition was given by Violet Unger, in 1972, (which can be read, alongside a graphic image of the cottages' state of disrepair and other colourful memories of life in Upper Gardner Street, in the 2016 Brighton Town Press / North Laine Community Association book, http://www.brightontownpress.co.uk/2016/09/new-the-north-laine-book/The North Laine Book, pp. 36-37). Urgent repair, demolition or rebuilding were quickly becoming the only two viable choices before the Corporation’s officials.

The results of demolition: Car park on the site of

nos. 6-12 Upper Gardner Street, May 1976.9

3. Architecture & Materials

Most of the buildings visible today date from either the 1840s or the late twentieth century. The variety of original structures offer evidence that Upper Gardner Street enjoyed a mix of industrial, retail and residential uses from its inception. Together with the school, this is a further reminder that for much of its history the street was a busy and important local thoroughfare.

The houses which retain something of their original form are clearly of a typical standard for lower-middle class terraces of the period. The walls are not made of stone or brick, but of a method common in Brighton: a cheaper, weaker mixture called ‘bungarooch’ covered over with a lime-based render. Some owners gave their properties additional visual status using subtle devices. One example is the use of ‘ashlar’ score-lines in the render, to imitate stone (as seen at number 24). Another example, lost to time, would have been the variety of doors; four panels were the norm, but six panels cost more and could indicate a touch of status.

Much of the 1840s terraced housing has been demolished and replaced by late-20th century houses (see numbers 6-9, 13-14, 18-22, 27-30, 36-37). There was clearly an attempt to replicate the style of earlier houses in the street, but unfortunately this was let down by lack of attention to scale and detailing. Regency and early Victorian architecture used a recognised set of rules for windows, doors and architraves – all relating to each other in terms of size and relative proportions. These important elements were not considered in designing these modern houses. A comparison of numbers 18 (new) and 17 (old) illustrates this point.

The 1840s houses which remain have undergone many modern modifications. No. 35 is a fair example of an original frontage. The most common alterations are to windows, particularly the use of PVC to replace some or all of the original six-over-six-paned sashes. However, some of these alterations merit some interest in themselves. See the early-20th century shop windows and fascias added to 1840s houses at nos. 3B, 15, 32, and 44 (the latter being a Maynards sweet shop in the early 20th century). No. 32 also demonstrates a 1920/30s attempt to ‘modernise’ the appearance in tune with the `Tudor-Bethan` timbered style fashionable at the time. It is certainly rather unusual to see such an attempt at increasing the visual status of a small existing terraced building in this way, and is perhaps explained by the building’s use as a shop.

Number 32 Upper Gardner Street in 2017

Along the East side of the street there remains evidence of the houses’ original basements, although the narrow pavement openings have been covered over by glass or masonry. There is one very worn coal hole cover outside no. 15, indicating the likelihood that houses were built with coal cellars in front, under the pavement. Most have since been removed or covered and the pavement made good.

The industrial premises are noticeably different from their neighbours. Nos. 3 and 3A form one building, with a higher roof-line than the house at 3B, a full-width loading entrance and a loading bay on the upper floor. Nos. 4A and 4B, ‘The Old Stables’, were built for the carrier R S Sayers in 1865 and has significantly higher internal ceiling heights and extends back much further than the neighbouring dwellings (as evidenced by the large, double-pitch roof, visible behind the parapeted front roof). The large industrial windows and central loading bay date from the late-19th or early-20th centuries. To the left, the ‘North Laine Antiques and Flea Market’ appears to have originally been a shop, converted to trade or light industrial use in the early-20th century. Across the road, the height, size and large industrial windows of number 39 indicate that this building was built for industrial use, although the date is uncertain, the industrial full-width sliding door is certainly late-19th or early-20th century.

R S Sayers’ 1865 warehouse, “The Old Stables” at no. 4 Upper Gardner Street.

Note the red paint on the road surface, marking the modern street-market pitches. For the origins of these fixed pitches, see section 6 for Harry Cowley, the 'King of the Barrow Boys'

Another prominent building is the Victorian Infants' school at no. 40. It has retained most of its distinctive historic character; the ‘modified classical’ decorative elements, such as the fluted columns on the doorway and name plaque, are very typical of late-Victorian detailing, still being used for significant public buildings at the time of the 1887 alterations. Sadly, the more recent (residential) roof extension looks top-heavy and bulky in relation to the historic structure below.

Plaque on the wall of the Central Infants School, 2017

The ‘Heart and Hand’ is an interesting and externally well preserved example of a late 19th century public house. Locations at street corners were favoured because this facilitated the typical internal L-shaped layout of the bar areas, and also the `hierarchical` subdivision of internal spaces – i.e. private bar and public bar. Note the separate entrance door to the side. The pub retains some excellent original ornate glass windows, and most of the original green glazed external tile work. To the pub’s right is a very narrow house, a tell-tale infill to the original passageway leading to stables and stores behind number 44.

The Heart and Hand pub, 2017

4. Ownership Patterns

The Borough Corporation’s extensive purchase of property in Upper Gardner Street during the 1940s, 50s and 60s has left a detailed set of ownership deeds in the public domain. Properties on both sides of the street typically trace their ownership back to Thomas Read Kemp, the local landowner whose development of Kemp Town would eventually bring him financial ruin.

On the East side of the street, examples include nos. 11 & 18. While Kemp owned the land on which both were built, he sold the former in 1827 and the latter in 1833, both to developers who would build properties on the sites.10

There is no indication that the owners of these, or any other residential properties in the street, lived in their houses during the 19th century; this working-class neighbourhood has all the appearances of being tenant-occupied from the beginning. No. 11 was stated in 1904 as being let “to Mr Marriott on a … weekly tenancy at 10/- per week,”. Mr ‘Merrett’ (as he appears in the 1891 and 1901 census) clearly lived at the property for some time with his family, while his landlord changed several times. Elizabeth Morgan already gave her address as 11 Upper Gardner Street when she bought the property in 1925, indicating she may already have been the tenant there (although she doesn’t appear in local directories for that address until around 1940). Mrs Morgan would eventually complete her sale to the Corporation in 1954.11 No. 18 shows a similar journey, in that owners’ names do not match those given by residents on the census returns or in local directories (indicating that no. 18 was let to tenants), until Alfred Cornford bought and occupied the house in 1918, remaining until at least 1951.12

Several properties on this east side of the street were owned in the late-nineteenth century by the Tucknott family, owners of the large printing works at 7 Kensington Gardens from 1862. In 1867 they bought no. 12 Upper Gardner Street, developed a passage to allow access to and from the rear of their works (made necessary, presumably, by the narrowness of Kensington Gardens, unsuitable for the new cart and pony used to deliver printed materials to customers) and by 1878 this passage was roofed over.13

On the death in 1898 of family patriarch John Tucknott, their properties in Upper Gardner Street were sold. No. 12 was purely a commercial premises and was sold to the Peters family, furniture dealers, living in the old Tucknott house in Kensington Gardens, and would be an early Borough Corporation purchase in 1942. Nos. 8-10 were sold by Tucknott’s executors to George Andrew Brown, a 'dealer in birds' based in North Street, who continued to rent them out, until selling to the Corporation in the 1950s.14

Another typical ownership situation is illustrated by no. 27. In 1956 it was owned by Mrs C Stevens, widowed wife of Harry Stevens, a fishmonger who, with his father before him, had traded on the premises since 1891. She ran the shop on the ground floor (albeit only on Fridays and Saturdays), and let out the living accommodation upstairs to the Newton family (Arthur, Annie, and four children).

Despite the property’s small size, outside toilet, and the presence of two smoke holes in the rear yard for curing fish, its condition was described as ‘good’ in May 1957. It seems that judgement was temporary, to say the least, since by 1961 the Corporation, as owners, were letting the property for storage of second-hand goods only. Amusingly, it is not just individuals who struggle with incorrect utility bills, as in July the Borough Estates Surveyor was forced to contest a charge for water services on the property, despite it having no mains water or w.c. for almost 20 years. He added the property was “in a dilapidated state and soon to be demolished”.15

5. Notable Buildings

By far the most significant buildings in the street from the point of view of residents were the Infants’ School, where their children were taught, and the Durtnall’s warehouses, which provided employment and constant activity.

The School

In 1811, the Church of England established the National Society for Promoting the Education of the Poor in the Principles of the Established Church. The building in Upper Gardner Street housed the Infants Department, set up in 1826 and part of the same organisational structure as the Central National School in Church Street, which housed the Junior School. We will explore the organisational life of the school under ‘Life and Work’ below, focusing here on the building itself.

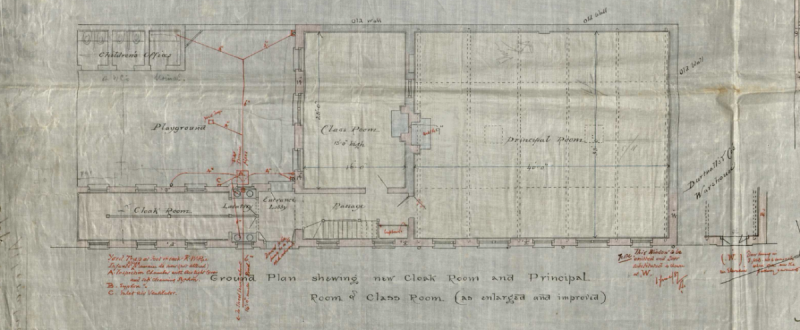

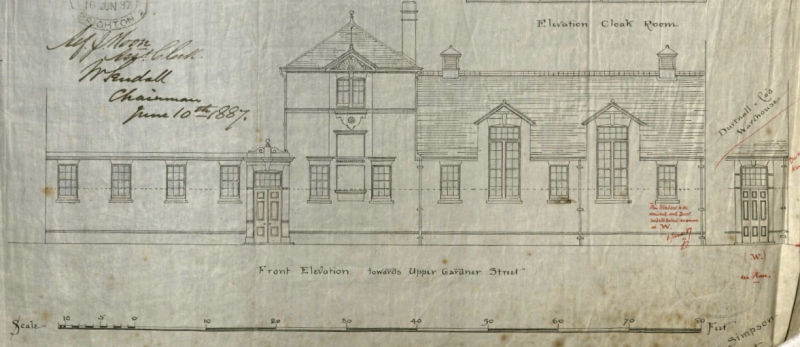

Initially the school comprised a simple two-storey central classroom block, with a ‘principal room’ or hall to the right, and a playground to the left, with outdoor privies in the far-left corner of that playground. In 1887 it was substantially enlarged, with a south wing added to the left of the entrance, housing cloakrooms and indoor lavatories. The main class block had an additional storey added to house a new classroom, the roofline of the principal room was raised to match, and the ‘entrance yard’ previously separating that principal room from the street was now enclosed and roofed.16 As the plaque on the front of the building still testifies, this represented a generous investment by the local community, and it was re-opened with due fanfare by Elizabeth Mary, Countess of Chichester.

Ground Floor plan and elevation from the 1887 School extension17

During the Second World War the building’s roof was requisitioned for use by local fire-watchers and the Infants department moved to Church Street. As it turns out, they were never to return, with children being moved to new schools elsewhere after the war. In 1945, the Upper Gardner Street building was leased to the Central Boys’ Club on a notional rent. In 1963 new toilet and shower facilities were added, including a changing area with lockers and basins, and an entrance vestibule between this block and the old central ‘class room’ tower.18

At some point (presumably after he bought the Theatre Royal in 1984), the site was re-named the 'David Land Arts Centre'. Its listings on many concert-ticket websites attest to its use as an arts venue. During the late 1990s it was re-named for Ray Tindle (presumably the knighted local newspaper proprietor, although his link to Brighton is hard to trace, and the North Laine Community Association celebrated their 21st birthday there in 1997. Around 2002 it was sold for conversion to residential flats, although the developers appear to have ceased work before it was completed. In May 2006 a group of squatters moved in, opening a vegan cafe and community space. They made a video about that process, viewable here. They willingly departed in 2007 as the council approved use by "Little Dippers," a group for mums and babies learning to swim, who continue to use the space, still partially developed, at the time of writing.

Durtnall’s Warehouses

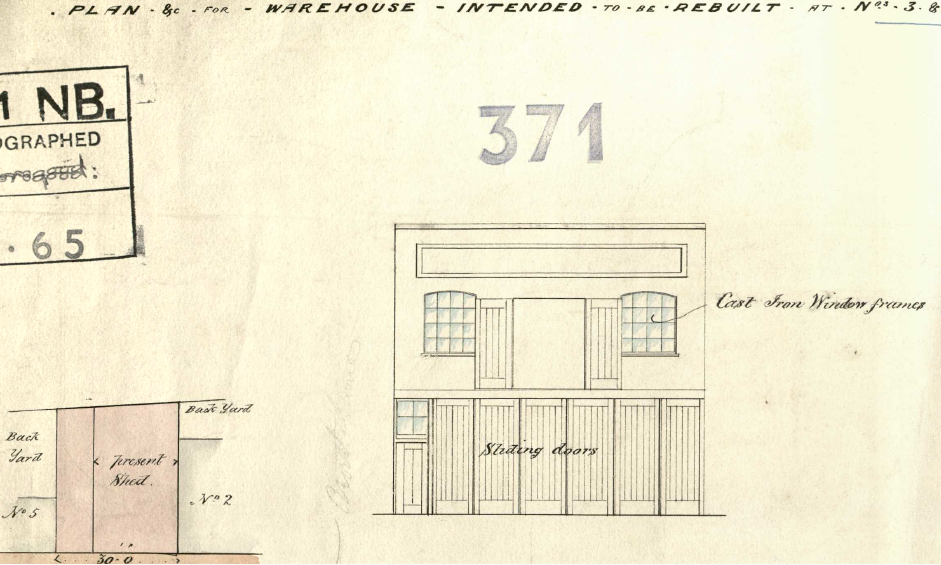

Turning to the warehouse buildings, R S Sayers, the tenant of nos. 1-4 since 1838, built a “shed” on the site by 1863, and it was he who commissioned the present warehouse building for nos. 3-4 in 1865. The picture below shows the building plan dated 8th November 1865, featuring the cast iron pillars and the sliding doors to street and to first-floor storage area that we see today.19

Block plan & front elevation for Sayers’ new warehouse.20

By 1875, Sayers’ debts forced him to sell the freehold, stock in trade, goodwill, business, etc. to William Wilkins & Frederick Danby, trading as Messrs Durtnall & Co.(carriers & removals) Ltd. Wilkins and Danby also occupied the large warehouse at no. 39 from this time, and business under their hands flourished. By 1889 they were able to pay off the £600 outstanding mortgage that Sayers had owed to Gainsford, and thus secured the title deeds.21 By 1903 both Wilkins and Danby had died, leaving Wilkins’ son HT Wilkins as company director, who would continue using the site “for the purpose of offices workshops sheds and vehicle sheds” until selling the business to R R Perry & Sons in 1949. Douglas Perry, the director at the time, would eventually sell the premises to the Brighton Corporation in 1965.

6. Residents

For most of its history, it was a transient community that lived in Upper Gardner Street, particularly in the nineteenth century. Occupants’ names (from census returns and published street directories) change every few years for most properties, unsurprising given that few residents owned their homes.

There were, though, some exceptions. We have already had cause to mention the Stevens fishmongers at no. 37 (see ‘Ownership Patterns’, above). William Fell, an Irish shoemaker, and his wife Elizabeth (also in the shoe trade, from that industry’s centre in Northampton) had moved into no. 24 by 1871. Ten years later William had died, but Elizabeth remained (by this time called no. 26, but quite possibly the same property renumbered). When she died, her son and daughter shared the house and the daughter, Elizabeth, would remain, sometimes with a female boarder for company, until aged 87 in 1947.

A similarly long tenure was experienced by the Braidens at no. 16. Arthur Braiden, a wine merchant’s cellarman, moved into the house in 1905, later survived by his wife Edith Mary, then their son James and finally a ‘Miss Braiden’, who was still resident in 1973. Edith even had a lodger who stayed 18 years, one William Parsons, who kept himself to one room and would not allow anyone to enter, as recorded by the Coroner at his death in 1924.

The Maskell family (Walter and Minnie Louise, and their adopted son), china and glass repairers, were familiar faces at no. 8, then later at no. 20, from 1908 until 1954.

King of the Barrow Boys

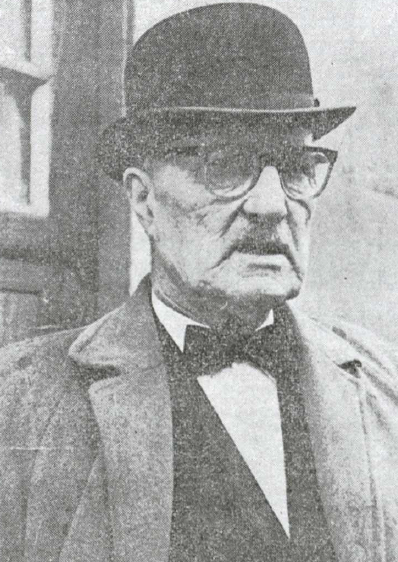

However, by far the most well-known person associated with Upper Gardner Street was Harry ‘the Guv’nor’ Cowley (although there is no evidence that he ever lived in the street). A larger-than-life character, he was known for his typical outfit of bowler hat, bow tie, trimmed moustache and drooping cigarette.

Harry Cowley, pictured in the Brighton Evening Argus, 6 March 1971

Born in 1891, his life was well documented by a number of obituaries in the local press on his death, aged 89, in March 1971. The most comprehensive can be found in the Brighton and Hove Gazette of 12th March.22

It details Harry Cowley's early life in Brighton, knowing poverty and collecting old bread from hotels to feed his mother and siblings. His social activism took off after the First World War, making speeches and leading marches, demanding jobs for the de-mobbed unemployed. At this time he founded his famous ‘Vigilantes’ group in Tichborne Street to ‘snatch’ empty homes for occupation by the homeless. He renewed this Vigilante raiding in July 1945, seeing that homes were being bought speculatively and deliberately kept empty to raise their sale value, while the wives and children of serving men who were able to pay market rents remained homeless following bomb damage. With the council unable to requisition houses without notice or red tape, their delays led Cowley to direct action, seizing homes and 'installing' new families before the police could intervene.

Cowley’s fame in Upper Gardner Street stems from his role as 'King of the Barrow Boys.' Himself a stall holder for 50 years, in the 1920s he organised his fellow street traders, helping them fight plans to eject them from Upper Gardner Street and into expensive, enclosed premises in new market buildings elsewhere. Protesting (even blockading streets), they “fought for and eventually obtained the licences which were to ensure their safety”. These licences entitled traders to a fixed, numbered pitch on the street, still demarcated by painted rectangles today. This ended the brawling, anarchic rush for unmarked pitches which had led to threats of closure for the street market, and threatened the safety and livelihoods of reputable traders, especially the elderly. Harry Cowley continued to attend the Upper Gardner Street Traders’ Association annual tea at the Corn Exchange into his declining years.23

(Read more about Harry Cowley in this QueenSpark book: Who Was Harry Cowley?)

7. Life and Work

Our available sources focus on two aspects of life in Upper Gardner Street: life at the Infants School / Boys’ Club, and the extant Coroner’s reports, many of which, sadly, concern the deaths of children.

The School

The Central National School trustees accounts commence in May 1818, and show the steadily accumulation of donations from local residents and the outlays to builders, teachers, and printers, as well as awards to individual pupils. Issues around charity fundraising and transparency are clearly not new; there is at least one instance of collector’s ‘default’, i.e. a collector keeping donated funds for themselves.24

The National School’s annual reports inform us that the organisation maintained at least eleven institutions including the Central schools in Church Street, the Branch schools in Warwick Street, and three Infant Schools, of which Upper Gardner Street was one.

Numbers of pupils attending seem to have fluctuated considerably, in Upper Gardner Street there were 260 children in 1828, only 82 by 1853, but 164 by 1859.25 Donations must also have varied, as in June 1885 Revd. Hannah, the Vicar of Brighton, was forced to issue a circular appealing for subscriptions, noting that there was a shortfall of £482 on the National Schools’ operating expenses and that if local donations fell there was a danger of losing a portion of their government grant, which aimed to match, not replace, local funding.26

Glimpses of life in the school in the twentieth century can be glimpsed through the Manager’s Minutes for 1938-1967. That they are collected within St Peter’s parish records, rather than state education records, reminds us that the school was first and foremost a means of inculcating religious knowledge in children and regular diocesan inspections recorded the state of the children’s religious knowledge.

By July 1938 the diminishing number of ‘scholars’ was noted with regret; at this time there were 30 children in a class of 6-7 year-olds. Conditions were still spartan; only in 1939 did the staff gain a room of their own (converted from a store room), with a single gas ring and heater. Education wasn’t all rote learning, as at the same time an empty room was dedicated for teaching crafts.

At the outbreak of war, the school was only allowed to stay open on condition that there were safe places to shelter during air raids. The Education Committee wanted children to use the public shelter under the library, but school managers were concerned about the danger to children while in the streets on their way to the public shelter (which for young children could take some time) and the lack of special facilities or safe accommodation for children in that shelter. They persuaded the Committee that the school hall was safe enough, so long as the entrance was suitably sand-bagged.

In July 1940, The Blitz, and the lack of air-raid shelter accommodation at Upper Gardner Street, led the Infants Department to move into rooms in the Central School in Church Street. The following March, all the Infants Department equipment followed, as the school building was needed for fire-watching teams. Although intended as a temporary measure, the pupils’ exile was lengthened when, in 1943, it became clear that the fire-watchers had managed to damage the structure and “persons unknown” had taken advantage of the vacant school to store furniture.

The Boys’ Club

Into this situation came a letter in July 1945 from Major G W Stapley, chairman of the Brighton, Hove & District Council of Boys’ Clubs, asking for the use of the Upper Gardner Street building as a new club venue and promising to meet all the costs. Unsurprisingly, “the [school] managers gladly consented,” and asked the Local Education Authority to remove the remaining furniture. The Boys’ Club would eventually be asked to pay a “nominal” rent of 10/- a week, in return for “use of the building until such time as they are required for educational purposes,” which was already envisaged as a “very unlikely circumstance”.

Management responsibility for the National Schools would pass in March 1967 to the new St Paul’s school. In the meantime, the Boys’ Club took on the mantle of local social hub for children and, in 1955, even allowed Central School children to use the Upper Gardner Street yard as a playground.27

The memoir of Bill Hall, who attended the club and went on to a career as a sports journalist for the Brighton Argus, gives a vivid depiction of what it meant to him and other boys in the local area. The club itself was secular in outlook and practice, in contrast to the school that preceded it, and was part of the National Association of Boys’ Clubs. Joining in 1947, “creeping in at 11 when the age of entry was supposed to be 12,” he reports fond memories of the Club’s leader, a “thoroughly Brightonian ex-Grammar School boy” named Keith Bergin; “clean shaven, and not much older than some of our older members”. Somehow Bergin, “without any obviously boisterous display of disciplinarianism” was able to tame “the wilder element among the membership, who had driven [the previous leader] from the club by their street jungle attitudes and behaviour”.

For Hall, the club “was my home from home, where we became averagely expert at billiards, table tennis, board games (though not that often, their being considered somewhat sissy),” indoor basketball, and more often three- or four-a-side football, “played at a furious pace, and with no referee or restrictions on height”. This practice must have stood Hall in good stead, as he went on to represent the club in soccer, cricket, table tennis and basketball teams. He was part of the club team that won the 1954 Brighton Youth Football League Championship, with both Hall and his friend Ray Berry scoring in a 3-2 victory over Whitehawk Boys’ Club. The following summer, aged 19, he would leave the club and join the Brighton and Hove Gazette as Sports Editor.28

Brighton Central Boys’ Club football team, 1955

Hall is in the back row, second from left. Keith Bergin,

the warden, is seen at the right-hand end of the back row29

Childhood Deaths

Not all childhoods in Upper Gardner Street progressed so smoothly into adulthood. Among the Brighton Coroner’s reports we find several regarding the untimely deaths of children resident in the street.

William West and Annie Kelly were both only a few months old when they died, the victims of childhood disease, in 1903 and 1906 respectively. William was the son of Herbert West, a journeyman painter living at number 36. A “very delicate child” with inflamed lungs, he was seized with a convulsive fit one Saturday morning in March and expired in a few minutes.

His mother and her next-door neighbour’s daughter, Lizzie Cosham, (herself only 10 or 11 years old at the time) watched helplessly, able only to administer weak brandy and water as young William died before the doctor could arrive.30

Distressingly, Lizzie’s would witness another youngster’s death only a few years later when she was aged 14. Barman George Kelly and his wife Jennie were also briefly resident at number 36. Their infant daughter Annie had been in her usual good health at bedtime on Wednesday 29th August, but a convulsive fit on Thursday left her unconscious and, despite the attendance of two doctors, she did not improve and died on the Friday morning.31

The summer of 1930 would see two tragic accidents befall older children.

Ronald William Ernest Heritage, the ten-year-old son of William Heritage, a clerk at Durtnall’s, died at the family home at 38 Upper Gardner Street on the evening of 11th July. A bright but frail child who had often complained of headaches, he had been kept home from school all week on this account. Finally able to get out of the house, he had gone that afternoon with his 16-year-old friend Walter Maskell from number 20, to the children’s playground on the Level. Left giddy after a turn on the swing, he unwittingly walked in front of Walter’s 14-year-old sister Rose on the next swing and had been struck by her foot, “knocking him to the ground, whereby he sustained a fracture of the skull”. The only sign visible to his friends and to Ethel Rabbitts, a visiting Londoner who stopped to help, was Ronald’s dazed state. Unbeknown to them, intracranial haemorrhage had set in. Taken home, Ronald felt sick, and was unable to recall for his grandmother how his injury had occurred. His condition worsened over the following two hours. Again, the sent-for doctor was unable to save him.32

Harry Lewis Coleby would meet his death through another accident that same summer , just a couple of hundred yards from where Ronald (whom he must have known, at least by sight) had died. Aged 13, he lived with his mother Clara and (step)father Harry Stevens, the fishmonger at number 27.

On the afternoon of Friday 22nd August, having finished his week’s lessons at Pelham Street school, he took out his newly-constructed 'box trolley' (a box attached to four pram wheels) for a spin. Reaching the bottom of Church Street and turning into Pavilion Parade, passers-by saw him attempt to steer around a large tree in the pavement. The rope attached to the front wheels for steering broke, causing his cart to run into the road and straight under the wheel of the no. 8 Tillings Omnibus. Although only travelling at 12 mph, the driver was unable to stop in time and Harry’s head and left leg suffered serious injuries. Despite a policeman’s rapid application of a tourniquet to his femoral artery, he died the following day at Royal Sussex County Hospital.33

8. Trade

Street Directories, the precursors to the Yellow Pages or phone book, give an indication of the street’s resident trades over time.

The Post Office Directory of 1846 shows trade focused at the south and north ends of the street, with grocery dealer and baker Stephen Fielder at no. 1; another greengrocer next door; opposite and on the site of the future Heart and Hand pub was John King, “corn dealer and beer retailer”; with another baker next door; and a cobbler and a furrier rounding out the list.

The list of specialist trades grows through the nineteenth century to include a sign-writer, an electro-plater, a glass repairer, and a hairdresser. By 1900, most residents paid to have their names in the directory, whether promoting their trade or not. Many list no trade, suggesting the trend toward paid employment rather than work on one’s own account.

Some premises are now owned by businesses, such as Durtnall’s, and the Forester’s Arms pub at number 21 (see more below). F G Smart at number 12 is a “printer”, presumably connected to the Tucknott works that owned the premises. Only John Merrett the bootmaker at no. 11, Harry Bleach the butcher at no. 20, and John Crouch the shoemaker at no. 42 continue the practice of home-based self-employment.

By 1951 the old variety of sole proprietors had more or less vanished from Upper Gardner Street. Several antiques, furniture and wardrobe dealers traded from the warehouse buildings, a couple of shopkeepers lived at nos. 11 & 12 and Harry Stevens still operated a fish shop at no. 27. The only other occupations listed are Mr Vickery the Boys’ Club warden and R R Perry & Sons the decorators’ merchants at nos. 1-4.

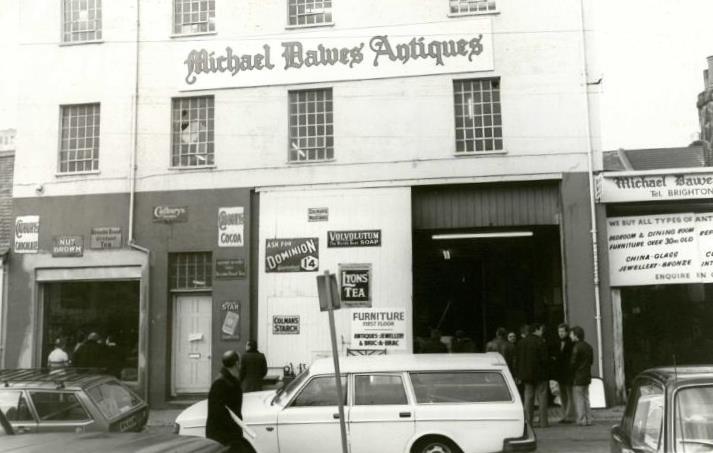

The antiques trade has long roots in Upper Gardner Street.

This is the old Durtnall’s warehouse at no. 39, pictured in January 197634

The same building in 2017, occupied by the Silo restaurant

Of the Heart and Hand at the junction with North Road and the Forester’s Arms at number 21, the former still stands. In 1809 it was empty land, “in the North Butts, in the North Laine, Brighthelmstone” and in a lease of 1836 two cottages occupied the site.35 As described above, the address (given as no. 54 in 1846, and no. 53 in 1847) soon hosted a “beer retailer”. However, thereafter the street numbers no longer reach such a high number, suggesting that the property was re-listed as a North Road address, and disappears from the Upper Gardner Street record.

The Forester’s Arms appears to have been a commercially unsuccessful and short-lived enterprise. First appearing in 1864, it disappeared by 1907, not long after the tragic suicide on the premises of Mark Lindup, landlord for a few weeks in the spring of 1905.

Formerly a publican in Preston Street, Lindup bought the licence at the end of March, claiming (according to a clerk from the brewer, Messrs Robins) that he had a plan to attract custom to this declining public house. It seems he was suffering some form of depression already or it rapidly set in, for Harry Stevens, the fishmonger opposite, reported his lonely lifestyle and “despondent” state and no business was forthcoming. Despite appearing “as usual” when he wished Stevens a good morning at 8 o'clock on 8th May, he would be found at lunchtime hanging by a rope from an upright in his own bar. A letter written to the Coroner by a Mr H Richards (connection unknown) gives one interesting judgement on the pub trade at this time and is worth quoting in full:

“I consider it only right that you should be made acquainted with the fact that the poor unfortunate man upon whose death you will hold an inquest this afternoon was driven to the sad and untimely [?] owing to the manner in which he had been defrauded by the brewer Messrs Robins, by inducing him to invest his small savings in what is nothing more nor less than a trap for the unwary, and the licence of which is retained only to put [?] into the pockets of these brewers and the public house brokers. The Forester’s Arms has never had any business, and you will be doing a just act if you advise the Justices to refuse a licence to this house in future. Morally Messrs Robins are responsible for the death of this poor old man who during the whole time he was in the house took 1/- 8d only, and this so preyed upon his mind that he was driven to the rash act which unfortunately terminated fatally.”36

The Street Market

The trade for which Upper Gardner Street is best known is, of course, the Saturday street market.

Developed due to the council’s need to move traders from ad-hoc pitches in Bond St. and Gardner St, the market formalised and created safer places and times of work for traders and customers alike. Upper Gardner Street was already the venue for meetings of a number of ‘barrow boys’, making it the ideal venue for the centralised trading space.

As described above (under ‘Residents’), much of the credit for this formalisation and for the formation of the Upper Gardner Street Traders’ Association which agitated for it, is due to Harry Cowley. He and his wife Harriet ran a second-hand furniture stall on the street for 50 years, and he was involved in setting up pitches on The Level for the Oxford Street Traders until the Open Market was built.

Once formalised, the market operated with 92 numbered pitches, each of which could only be used by the trader holding the appropriate numbered licence. Pitches were popular, only becoming available when an existing stallholder surrendered their licence, or died - at which point their licence would be offered to the first person on the (substantial) waiting list. Licences would automatically become forfeit if the pitch was left unused; failing to turn up and trade for over a month would lead to a hearing, where the licensee had to explain their absence and justify their continuing holding of a licence.

In the 1982-83 season, the annual fee for a licence was £70. While most of those who bought licences were from around Brighton and Hove, few were actually resident in Upper Gardner Street. Many sold a variety of antiques or second-hand goods, principally crockery, clothing, furniture, or other household goods. There are a few specialists, including a fruit and veg stall, one dedicated to medals and military antiques, jewellery, tools, and craft-work.37

Street Market stalls, Upper Gardner Street, 1940s38

The market has certainly played host to a number of colourful characters over the years. Writing for the North Laine Runner in 2007, local resident Paley O'Connor spoke to current market stall traders to hear their stories.

One remembers that, “outside the Heart & Hand was Ernie Winton, who sold only bananas - stacks and stacks of 'em all day long". Then there was Mr Baker, who sold cabin trunks and theatre props. Mrs Morgan, who lived in a basement in the Old Stables (no. 4), sold “a jug of tea for sixpence and a bread roll for a penny”. Gordon Fowler had a crockery stall. “He'd never use a table and always put his wares on the ground. People would ask him the price of something and if they didn't accept it and made him an offer, he'd pick it up and smash it! He didn't care. In the end people used to make an offer just to see him do it.”

Another recalls, “There was an 'odd stocking stall' and what was known as the 'pot luck stall'. It sold only tins, often dented and always unlabelled. You never knew what you were getting - could be peaches or dog food! The council eventually refused to give him a license, which resulted in uproar from his regulars.” One remembers that, “Upper Gardner Street Market used to be much bigger. It included a covered area in what is now Brighton Antiques Wholesalers, which went through to Diplock's Yard running between the Market and Queens Gardens … One of the lock-ups was used to keep all the stalls in during the week.” 39

Memories such as these remind us of the importance of oral history, and of our own memories, which retain much of the essential material that gives life to the official documentary evidence retained by public authorities.

9. Conclusion

Many people passing through Upper Gardner Street today will receive the impression of a street that time has passed by, with the retail and light industry of previous decades now clustered in other streets nearby and the properties retained for quieter residential purposes.

Such nostalgia should be balanced by the recognition that the lives of today’s residents are considerably healthier, safer, and more comfortable than their forebears’. No longer will the census show 174 people squeezed into this street; families today enjoy substantially greater living space and better domestic facilities in houses largely protected from cold and damp. Should disease or accident befall, the available medical care can be delivered faster and with more expertise and free of cost - in contrast to the tragic stories from the Coroner’s records.

As we noted earlier, there remain signs of commercial life in the street, from the continued commercial use of no. 39 (currently housing the Silo restaurant), the survival of an antiques & flea market at no. 5 and, not least, the fresh paint delineating market pitches on the road surface anticipating the weekly Saturday influx of life and noise.

The market, while considerably smaller than in its mid-twentieth century heyday, is certainly alive and well, with stalls filling the street and a fair crowd of shoppers in evidence. The wares no longer cater to the essential clothing and household needs of locals, however. There are a number of clothing stalls, focusing on the current trend for retro and recycled fashion, as well as those selling tourist sunglasses. The smattering of antiques stalls are now supplemented by a high number of artistic outlets. Stalls sell handmade cards, paintings, secondhand books and music, and jewellery. These clearly reflect the prevailing tone of the North Laine as a whole in the early twenty-first century; vibrant, creative, and passionate about all that is local, unusual or distinctive.

Street Market stalls, Upper Gardner Street, 2017

Ian Walden, June 2017

References

1. East Sussex Record Office, ref. DB/D/8/2175 2. ESRO, ref. DB/D/8/2182 3. ESRO, refs. DB/D/8/3015, DB/D/8/3226, DB/D/8/3264 4. ESRO, ref. BH/B/4/67/4 5. ESRO, ref. DB/A/1/283 6. ESRO, ref. AMS6649/4/27/25 7. ESRO, ref. DB/A/1/283 8. ESRO, ref. DB/A/1/282 9. ESRO, ref. BH/H/20/22 10. ESRO, refs. BH/G/2/1072 and DMH/ACC8577/46 11. ESRO, ref. DMH/ACC8577/46 12. ESRO, ref. AMS6853/2/1/1 13. ESRO, ref. BH/G/2/2735 14. ESRO, ref. DB/A/1/282 15. ESRO, ref. DB/D/7/2483 16. ESRO, ref. DB/D/7/2483 17. ESRO, ref. AMS6649/4/24/17 18. ESRO, ref. DB/D/7/371 19. ESRO, ref. DB/D/7/371 20. ESRO, ref. BH/G/2/4641 21. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1924/34 22. ESRO, ref. BTNRP_BH500321 23. Who Was Harry Cowley? (Brighton: Queenspark Books, 1984, revised 2003), thefedarchive.files.wordpress.com/2012/11/who-was-harry-cowley.pdf [Accessed 15/06/2017] 24. ESRO, ref. E/SC/16/2/6 25. ESRO, ref. ESC 16/5 26. ESRO, ref. PAR277/25/3/2

27. All of the above sourced from ESRO ref. PAR277/25/3/1 28. ESRO, ref. ACC 12154/1 29. ESRO, ref. ACC 12154/2 30. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1903/40 31. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1906/114 32. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1930/59 33. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1930/77 34. ESRO, ref. BH/H/20/22 35. ESRO, ref. ACC8396/5/2 36. ESRO, ref. COR/3/2/1905/64 37. ESRO, ref. ACC 8448/1 38. Brighton Museums, Photographic Print, brightonmuseums.org.uk/discover/collections/collection-search/?cblid=BTNRP_HA920457 [Accessed 15/06/2017] 39. O’Connor, P. Market Memories, North Laine Community Association, http://www.nlcaonline.org.uk/page_id__111.aspx [Accessed 15/06/2017]